.. depending on the steps you follow

A well-known quote attributable to Albert Einstein, reads, “If I had only 1 hour to save the world, I would spend 55 minutes defining the problem, and only 5 minutes finding the solution”.

Simply put, the more time upfront we spend properly discovering & understanding an issue, the more diligent we are in wrapping our heads around the symptoms a customer is reporting. We become less hasty to jump to a fix and should be able to eliminate areas we don’t need to investigate and isolate those which we do.

One way of thinking about this is “slowing down early in our thinking so that we can speed up later”; a concept that’s easy to understand in theory, but much harder to put into practice. There is a human proclivity to jump prematurely into action because, psychologically, we have a felt need to be “doing something” to feel productive. And, sometimes, this can be reinforced by others we work with, especially during a major outage when tensions are high, and someone is suffering impact. Consider when you have heard someone exclaim, “don’t just stand there – do something!”

This, of course, is a mindset that can quickly force us into reverse if we are not careful. To that end, Einstein was on the right track with his thinking. Not in the sense that we should take 55 minutes before doing something per se, but that we must take the time to define a problem well before we should attempt any efforts to solve it.

Slowing down and asking good discovery questions at the onset of an issue is the key to maximizing first time right, getting to restoration faster, minimizing rework in the troubleshooting process, and making efficient use of time, resources, and energy. This behavior is the hallmark of high-performing organizations.

- #1 is better problem-solvers: They are 163% more likely to be able to correctly identify and resolve the root cause of a customer’s issue.

- #2 is collaboration: They are 127% more likely to enable their customer service agents to enlist the help of different parts of the organization, partners, and customers in real time.

- #3 is they are self-service promoters: They are 36% more likely to offer self-serve for simple requests, empowering customers to answer more of their own questions.

When it comes to troubleshooting, slowing down to ask questions first before trying a fix not only improves team collaboration; it ensures more useful information gets gathered, which will translate to stronger reusable knowledge. Some of this is owed to the fact that, through this knowledge, we can help customers help themselves and potentially deflect a case from getting opened in the first place.

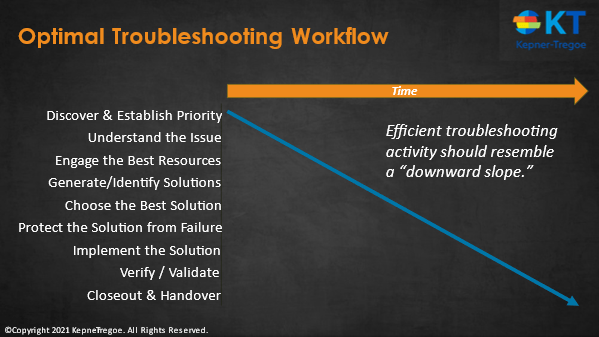

To that end, troubleshooting should follow a logical flow that, when mapped out, resembles a downward slope.

At the top of the slope, we should be focusing strictly on appraising the symptoms being reported, focusing on the “facts” of what is being observed and setting aside any assumptions of cause. It should not be until the middle point of the slope that we begin discussing possible causes and generating solutions once we have sufficiently clarified an objective problem statement and description. It is from these “expert facts” that we will home in on relevant clues for cause.

In the absence of gathering facts first, we risk problem-solving becoming one gigantic guessing game. Consider how many possible causes subject experts can come up with if asked to brainstorm without any context. Using the problem description, false causes can be logically eliminated until there remains a clear most probable cause that survives against the facts. This makes it infinitely easier to plan next steps and identify the appropriate restorative or corrective action that will resolve the issue at hand. More importantly, from all this there will be a complete story to tell around what happened and how the solution came to be, which sets the stage for stronger continuous improvement.

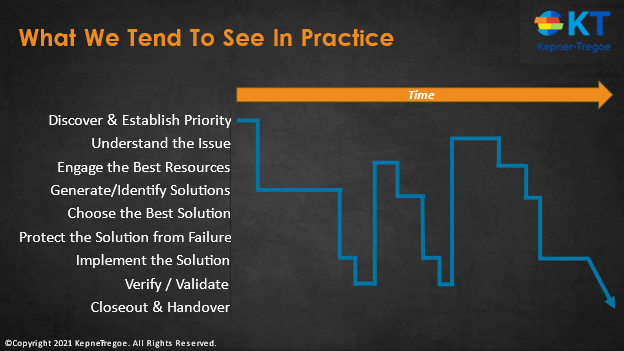

While this flow of logic makes a great deal of sense, in theory, experience tells us it is easy for many organizations to succumb to the “heat of the moment” when fires are burning and forgo the order of operations when it comes to good problem-solving practices.

When business impact is critical, anxiety is pervasive, and everyone has eyes on the issue, there is a natural tendency to jump into action and make assumptions that may not be based on evidence. The result can be substantial rework in the troubleshooting workflow, when “trial & error” fails to yield any fruit, and we follow a pattern of falling back to square one after what is likely to be a substantial period of “dead time” where valuable team resources wait around idly for actions to finish, some of which may turn up nothing productive. While eventually the dart may find the bullseye, the journey there can be a windy road fraught with high-cost activity and wasted effort.

As the saying goes, “the shortest path between two points is a straight line.” Where “A” is the point the customer calls and “B” when issue resolution has been verified, the way we get the straight line between both is by asking the right data-gathering questions, keeping assumptions in check, and making clear thinking visible along the way.

CHALLENGE: The next time you face a problem-solving situation at work, try using the Optimal Troubleshooting Workflow pictured above as a benchmark for what the team should be doing. When the team gets stuck, ask, “where are we at in the troubleshooting process right now, relative to the steps in the workflow?” For example, if people seem to be debating possible causes and generating solutions, yet there is no clear problem statement or description that has been made visible, perhaps it would be prudent to slow down and ask clarification questions before attempting anything else.

How often does your organization conduct post-mortems on problem-solving meetings, in the interest of scrutinizing the problem-solving process that was followed to gauge what worked well and where thinking could have been more productive?

In addition to using this workflow as an in-process tool, apply the logic afterward as a barometer of how the team did. Examples of follow-up questions that may prompt good discussion include:

- How much time did we spend discovering & prioritizing the issue(s) before jumping into problem-solving mode?

- Did we have the right resources in the meeting from the start? Was anyone there who did not need to be? How active was each person? Did we release team members when they were no longer needed?

- At what point did we transition to generating & identifying solutions? Was that before or after we had a documented problem description and understood the issue(s)?

- How effectively were we able to eliminate causes that did not make sense?

- How much time was spent testing or investigating theories?

- Did our problem statement reflect the actual cause-unknown symptom being observed, or did we lead in with an assumption of what we thought was happening?

- How much energy was spent thinking through the risks of a fix before moving ahead with implementation?

There are many more thought-provoking questions we can come up with. The point, however, is that problem-solving should follow a certain order of operations, as it is a process. And, if we are ever to get better at that process, as with any process, we must be in the habit of auditing our activities, both while they are in motion as well as after they have concluded, to ensure that we are following the right steps of the process in the proper sequence. If not, the consequences may be high: Costly rework from going backwards in thinking, decreased morale (and confidence) from lengthier investigation cycle times, and unnecessary actions that could have easily been avoided in hindsight.

If right now you are thinking, “my team can sure do better at this,” you might consider applying this Troubleshooting Workflow as a New Year’s resolution. If that sounds scary and you are wondering where to begin, reach out to us for a chat.