Which organization is more like yours?

FDA regulations will choke our business: Requirements, changing all too often, generate extra work and mountains of paper. FDA auditors have no understanding of our business and appear intent on slowing or shutting us down. We prepare for site visits in fear that some unknown discrepancy will earn us a Warning Letter. Our production is not like other manufacturing. Based in biologics, it is unpredictable, more an art than a science. We try to minimize reporting deviations, because the paperwork burden they generate is a distraction from what we must do here. Our deviation reporting is designed to satisfy the inspectors.

Compliance audits provide useful insights about what we can improve: Our business is run to maximize production efficiency. It is easy to document deviations, which is part of our systematic approach to continuously improving our operations. We proactively search for performance that deviates from our standards. We effectively prioritize the deviations we detect, assigning corrective action teams to find cause, develop solutions, and manage risks when we make changes. Concise, thorough documentation guides our improvement efforts.

There are probably no organizations that warmly view FDA audits. But in the current economic downturn, there is a growing need to reconcile these two perspectives in order to control costs and build new levels of efficiency. In healthcare manufacturing, no one can be oblivious to the need to protect public health and safety in the development, manufacture, and distribution of devices and pharmaceuticals. Yet many argue that regulatory requirements inherently impede efficient business process management. Much of the management effort directed toward FDA compliance reflects this tension. Often, the emphasis is on taking action—any action—to reduce attention from the FDA. Too much management time and attention spent on this approach to compliance is expensive and wasteful.

Resource-efficiency and compliance are not opposing forces. In fact, using systematic techniques to conduct and document investigations, implement corrective and preventive actions (CAPAs), and reduce operator error can help most healthcare manufacturing organizations improve compliance, cut costs, and achieve superior business results.

Systematic Corrective Action

An organization that seeks to efficiently maximize the use of its resources can and will reduce compliance efforts. Within such organizations, compliance means to minimize deviation from standards. These standards are consistent and predictable levels of performance for each manufacturing process which, in turn, serve as a guide toward a state of superior efficiency.

We propose a proactive model for achieving cGMP and QSR compliance: managing resource-efficient processes to provide predictable, documented results. At its core is a systematic approach for managing the CAPA to ensure that deviations are identified and resolved so that output standards are met (or preferably, exceeded).

The Logic of the Model

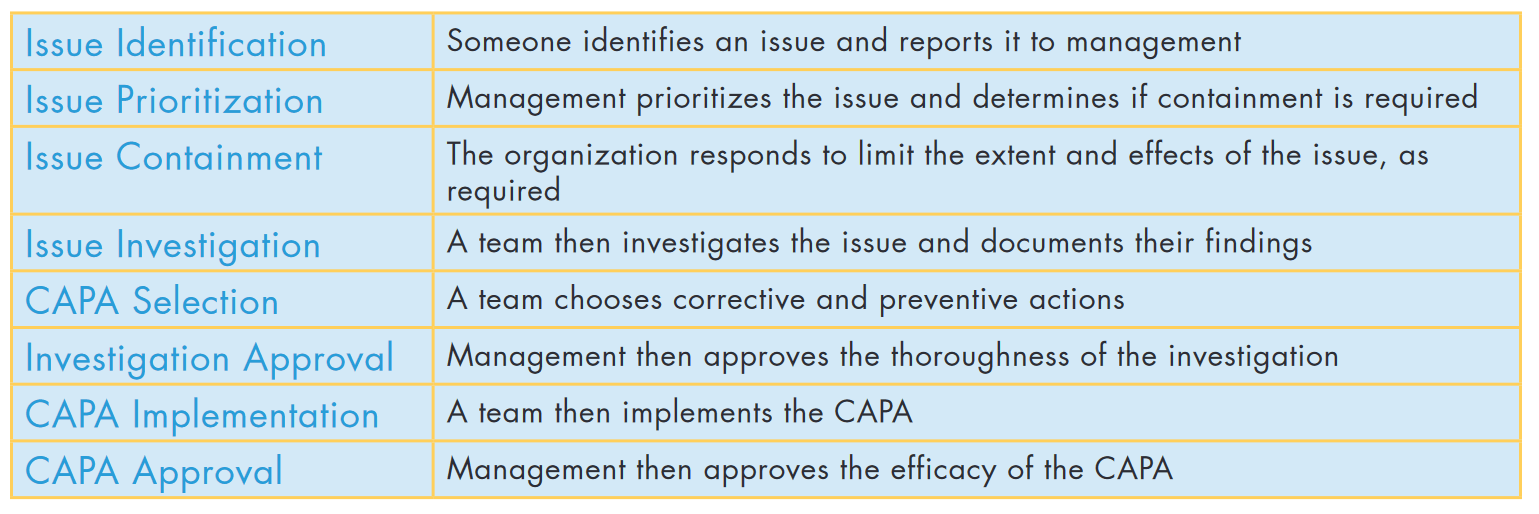

Most CAPA systems include the following steps:

A systematic process for completing each of these steps is at the core of our model for maximizing productivity and compliance. The challenge is that this systematic approach requires a level of discipline seen in few organizations. Complex management systems, sometimes belabored by the perceived conflict between compliance and efficiency, often work against, rather than for, effective action. Information systems are designed to manage the information flow by tracking each relevant document to meet FDA requirements. However, few systems make the vital leap between managing compliance documentation and improving business performance.

Using process thinking helps organizations to link CAPAs to operations systems and make the leap from compliance to business results. Since 1958, the gold standard in the effective resolution of issues has been Kepner-Tregoe’s four FDA-recognized processes: Situation Appraisal, Problem Analysis, Decision Analysis, and Potential Problem Analysis. They provide the basis for a Process Thinking Model that integrates compliance into operations by translating effective action into business results.

Issue Identification

Efficient and compliant issue identification requires early recognition to minimize the growth of the issue, good definition to minimize inappropriate responses, and then a punctual response to minimize the spread of the issue.

When people in your organization report non-conformances:

- How useful is the information they provide for understanding the scope and impact of the non-conformance?

- How useful is the data for tracking and trending incidents over time?

- How useful is the data for prioritizing non-conformances and determining appropriate next steps?

By using the Kepner-Tregoe Problem Analysis process, clients are provided with a framework for clarifying and documenting non-conformances accurately and concisely.

Case Study Example

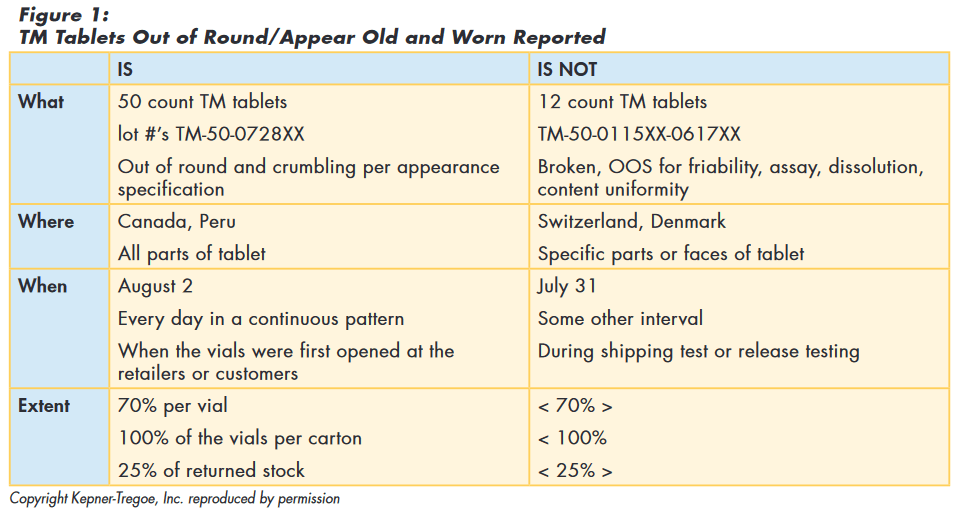

This case study provides an example of how an organization with an effective corrective action system would address a deviation. Shortly after launching a new product (TM tablets), the manufacturer received reports of customer complaints about bad tablets. Consumers provided the information that the tablets “didn’t look right,” and complaints were beginning to accumulate from several countries in which the manufacturer did business. Following the chain of logic and data, the investigation team quickly assembled the relevant data from internal consumer complaint reports.

Using problem analysis, the team summarized the data as shown in Figure 1.

Issue Prioritization

Prioritization begins with an accurate assessment of the deviation based on clear criteria that balance regulatory and business needs and effective routing to ensure a timely response, based on clarity of protocols. Relevant information and clarity of communication should drive both appropriate escalation and planning of the approach to the investigation.

When people in your organization gather to determine how to address non-conformances:

- How often are there differences of opinion about the appropriate next steps?

- How long does it take to determine the appropriate next steps?

- How frequently do people struggle with allocating limited resources to competing priorities?

Situation Appraisal: A logical framework for identifying and prioritizing issues. Bringing order and clarity to a complex environment, setting priorities, and planning actions to resolve each concern. This is especially important at the operations management level in identifying high priority and costly issues that require action. Effectively prioritizing resource utilization is one of the most important elements in a well functioning corrective action system.

Case Study Example

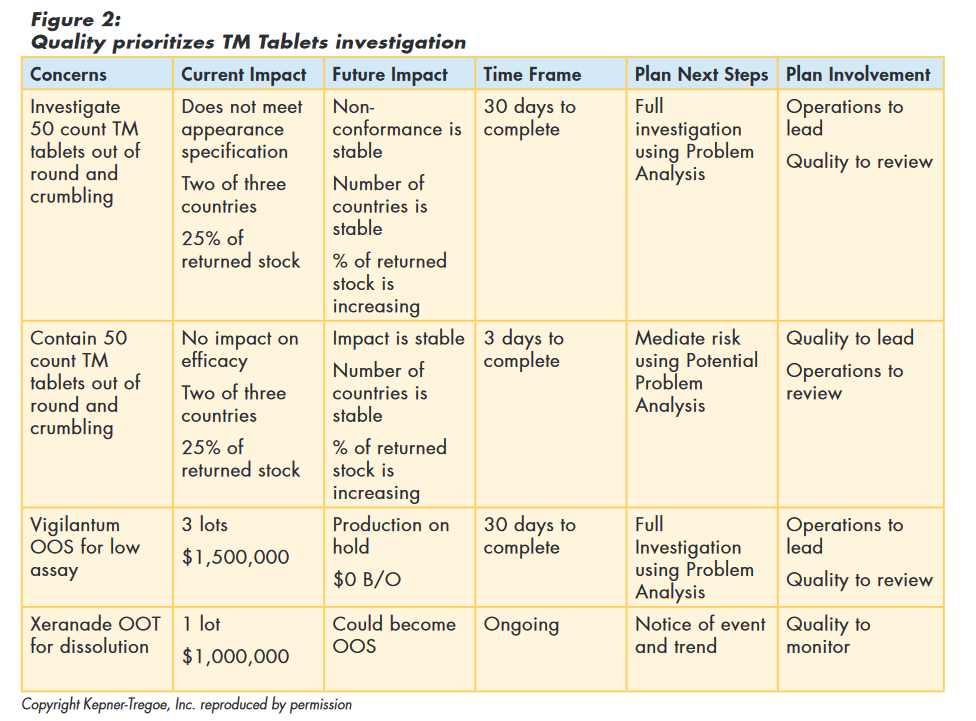

Quality reviewed the information provided by the investigation team, and determined that investigating the “out of round” tablets was a high priority concern relative to other issues. One team was charged with finding the root cause of the deviation. Another team was asked to make recommendations on how to contain the effects of the non-conformance.

Using the situation appraisal framework, Quality summarized the information and documented their thinking, as shown in Figure 2.

Issue Containment

Effective containment requires interim actions and contingent actions to limit the spread of any potential problems associated with the non-conformance.

When people in your organization initially react to a non-conformance:

- How timely are their responses?

- How appropriate are their responses?

- How well do their responses limit the spread of the non-conformance and its effects on your organization and your customers?

Potential Problem Analysis helps people efficiently identify measured responses to a non-conformance, and any potential problems or effects that might result.

Potential Problem Analysis: Avoiding Risks Inherent in the Solution. Anticipating risks that may arise from implementing a containment action and planning appropriate action before they become reality. Preventive and contingent actions are established to minimize risks, while promoting and capitalizing actions are established to extend benefits. Forward-looking organizations can often avoid most significant manufacturing deviations through disciplined use of potential problem analysis.

Case Study Example

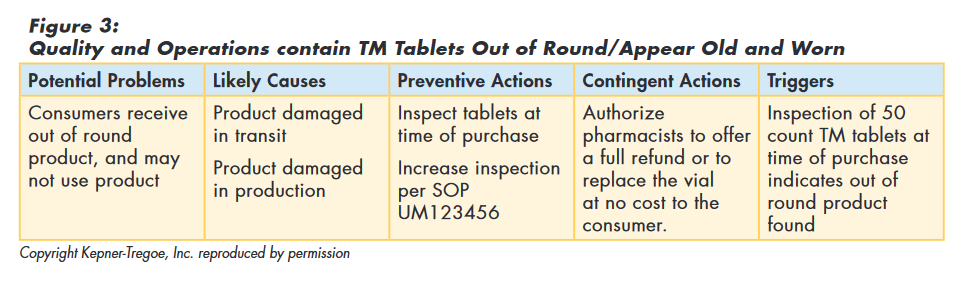

The team decided that as there were no reports or evidence of safety or efficacy issues, maintaining TM on the market was appropriate and that a re-call was not required. They did consider that if consumers continued to receive “out of round” product they might refuse to use it.

So the team used the logic of potential problem analysis to implement preventive actions to minimize the probability of customers receiving “out of round” tablets and planned contingent actions to minimize the seriousness if it did happen, as shown in Figure 3.

Issue Investigation

A good investigation leads to true cause. When people in your organization conduct investigations:

- How often do they get to true cause?

- How much time is spent gathering relevant data versus documenting speculations?

- How well do their investigations explain the logic used to determine cause?

Problem Analysis: Finding the Root Cause of Deviations. Investigating the cause or causes of failure. When something goes wrong, the question is: why? Problem analysis provides a powerful logic for understanding the root cause of performance deviations. Corrective action that drives business value rests upon a foundation comprised of an effective, systematic logic for finding root cause.

Case Study Example

A number of hypotheses had been generated about the cause of this problem, some based on fact, others on rumor. Senior management considered recertification of several vial and carton vendors, and discussed with operations management a thorough overhaul of the manufacturing lines.

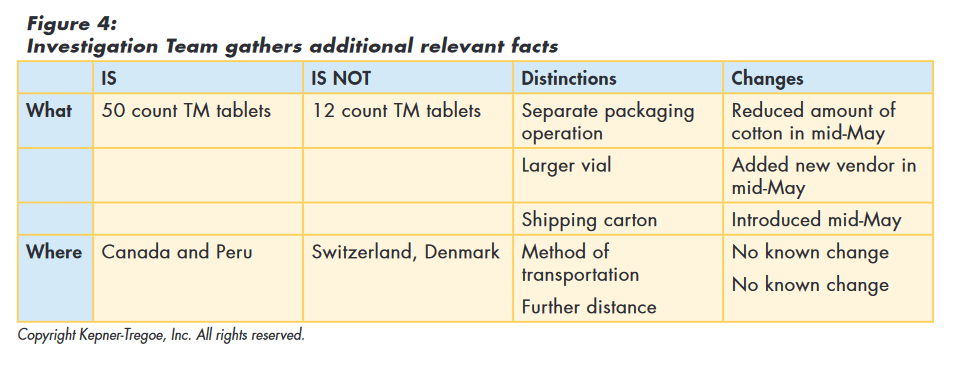

The team used the information gathered during the issue identification step to focus their search for additional information and identify relevant changes. Rather than looking for global changes, the team recognized that whatever caused the “out of round” issue only affected the TM in 50 count vials and then only those shipped to Canada and Peru. Using this approach they identified the following relevant changes as shown in Figure 4 below:

- Reduced amount of head space cotton in mid-May

- Added new vial vendor in mid-May

- Introduced new shipping carton mid-May

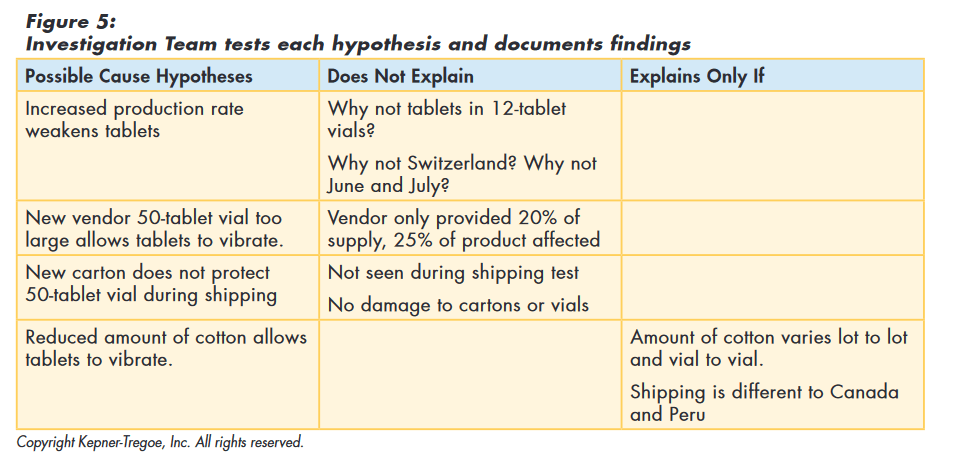

The team then tested the original hypothesis (and those they had developed) against the facts they had gathered to assess how well the hypothesis explained all those facts. The original hypothesis, as well as the new vendor, and the new carton, could not explain all the facts and were eliminated from consideration. “Reduced amount of cotton allows tablets to vibrate” best explained the facts. They also identified assumptions required to explain the cause and additional information needed to confirm true cause, as shown in Figure 5.

With these results, the corrective action team concluded that the most probable cause was cotton being stuffed too lightly in the 50-tablet vial, offering too little protection in shipping. The process provided the team with a focus for their additional data gathering.

To test this conclusion, the team suggested three, simple tests to confirm the true cause:

- Take samples to determine how amount of cotton varies.

- Determine actual shipping conditions

- Run vibration tests with plant stock to simulate shipping and handling with different amounts of cotton

These simple tests enabled the manufacturer to find the true cause of the deviation. The rigorous and timely application of Problem Analysis to the existing data prevented overhauling production or the adoption of other expensive alternative courses of action. A tightening of standards and improved operations reporting gave manufacturing management the necessary tools to prevent recurrence of the problem, improving both productivity and customer satisfaction. The analysis was added to the database for the operation. The well-documented approach satisfied the regulatory requirement for systematic root cause analysis.

Investigation Approved

Approvals should be based on clear criteria and support the performance system.

When people in your organization present investigations for approval:

- How many review cycles are required for approval?

- What information is provided to investigators to help them improve their investigations?

- How are people encouraged to complete thorough investigations?

Engineering the Performance System: Aligning Performance with Organizational Goals. Kepner-Tregoe’s approach to managing performance is based on the experiences of effective leaders who know that setting clear expectations for performance — and then helping employees achieve that performance — are the keys to sustaining competitive advantage. The approach centers on a five-component model (Situation, Performer, Response, Consequences, and Feedback) that has been consistently re-validated since its inception, and provides a practical, useful framework for understanding human performance.

CAPA Selection

A good CAPA is the best balanced CAPA chosen to meet the detailed needs of the specific nonconformance. When people in your organization recommend CAPAs:

- How often do CAPAs provide actions to remove true cause?

- How often do CAPAs recommend actions to prevent re-occurrence?

- How often do the recommendations address any risk associated with the CAPA?

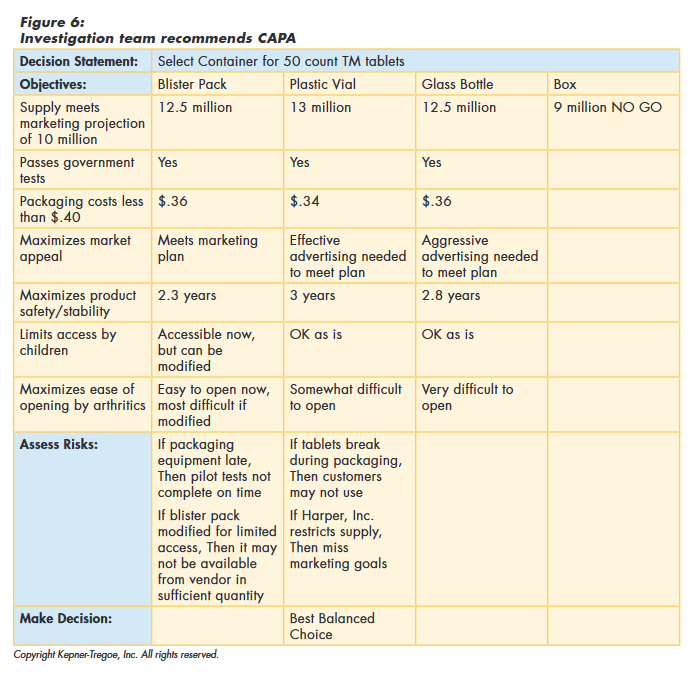

Decision Analysis: Selecting the Best Solution for the Deviation. Making choices between alternative corrective actions. Decision analysis is concerned with selecting the action that best meets agreed performance objectives, while managing the risks attendant to any change. Alternative actions may be known, or a new solution must sometimes be created. Senior management is often involved in sanctioning the actions that are adopted.

Case Study Example

To choose the best balanced CAPA, the team first identified and documented the needs of the organization and of all of the stakeholders. They evaluated the alternatives against these needs to identify the best performing. They then assessed any risks associated with the best performers, before making their final recommendation, as shown in Figure 6.

CAPA Implementation

There are two important aspects to implementation: Prioritization and scope management by the leadership team, and then effective implantation by the project team. When people in your organization implement CAPAs:

- How well/often are CAPAs delivered on-time, on-cost, and on-performance?

- How often do CAPAs overlap?

- How often does scope change?

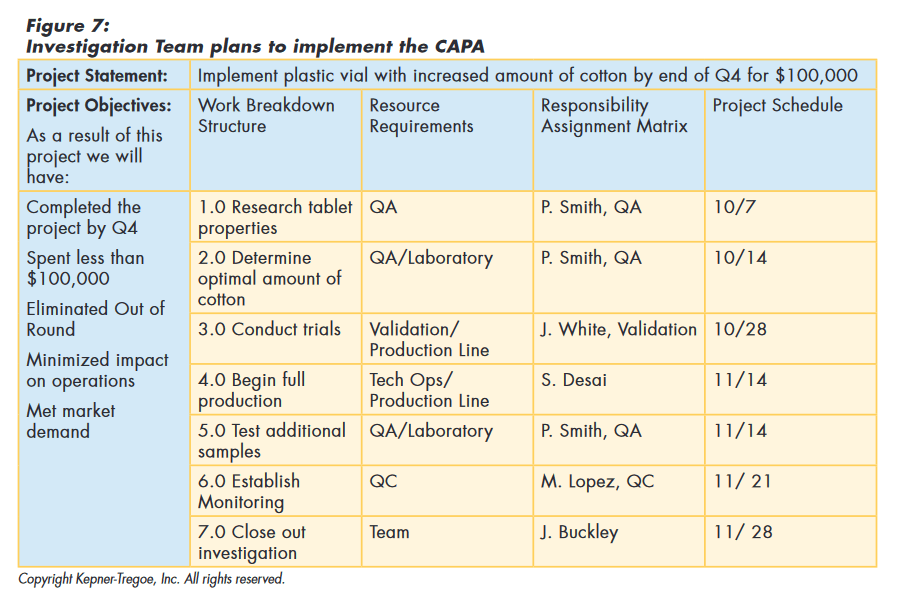

Project Management: Utilizing Resources Wisely to Implement Value Added Change. A good plan provides objectives that decision makers can use to prioritize changes and identify overlapping changes. A good project plan provides information on resources required so the value of the change can be assessed against the cost. A good project plan provides an accurate time line for when to expect completion so progress can be monitored.

Potential Problem Analysis: Avoiding Risks Inherent in the Solution. Anticipating risks that may arise from implementing a corrective action and planning appropriate action before they become reality. Preventive and contingent actions are established to minimize risks, while promoting and capitalizing actions are established to extend benefits. Forward-looking organizations can often avoid most significant manufacturing deviations through disciplined use of potential problem analysis.

Case Study Example

To implement the CAPA, the team considered and documented the goals of the project for the organization. They used these guidelines to determine the work needed to achieve the goals and the type and amount of resources required. This information was used to choose resources. Based on the availability of the resources, they put together a time table for implementation, as shown in Figure 7.

CAPA Approved

As with Investigations Approvals, CAPA Approvals should be based on clear criteria and support the performance system. When investigations and CAPAs are closed:

- How well is efficacy confirmed?

- How well is on-going monitoring established?

- How well are Team Members’ efforts appropriately acknowledged to encourage people to complete thorough investigations and implement appropriate CAPAs?

Conclusion

Production standards and FDA regulations (often supplemented by ISO and Baldrige criteria) are the foundation for compliance. These define what should occur. A critical objective in defining production goals, regulations and standards is that all terms are meaningful in the manufacturing environment, understood and supported in the organization, and can be realistically followed or achieved.

With acceptable standards in place, monitoring and reporting can compare planned performance with actual performance. Effective monitoring and reporting precisely specifies the nature of deviations, including their identity, location, timing, and magnitude. In addition, information about distinctions between successful and unsuccessful production operations must be effectively documented. The critical objective is identifying, on a short interval basis, all meaningful deviations between planned and actual performance.

Many corrective action systems lose their business value through weak controls. Often, they focus on extraneous information that is believed to be desirable to meet FDA, and perhaps ISO, requirements. An effective approach to CAPAs should continuously improve execution, as well as provide more accurate input to better plans. Critical objectives include:

- Prioritization of deviations for corrective action

- A disciplined process for investigating root cause

- Improving operations

- Minimizing the risks associated with change

The Kepner-Tregoe processes integrate compliance efforts into operations, making FDA compliance part of operations, the basis for continuous improvement, and a catalyst for operations excellence.

Information Technology and Process Thinking

Technology has exponentially increased the amount of data available for conducting and documenting investigations and finding root cause. But what about our ability to make effective use of this mass of data to resolve problems or prevent them from occurring? Add regulatory pressures to this mix and it is easy to see how organizations become FDA obsessed rather than business results focused.

Process thinking, like any logic, makes sense out of otherwise incoherent data. The four processes outlined in our Model improve CAPAs by helping to focus on the right data and objectively driving corrective and preventive actions. Process Thinking enables us to know where to look, what to look for, what to gather, what to exclude, and, most important, what to do. It must be acknowledged that ultimately process thinking is driven by the most powerful resource available to any organization: its people. How do people act within an environment of effective CAPAs and compliance? What specific methods do they employ as they perform daily to produce the organization’s business results? What do they think about when production deviations occur? What avenues can they take to set clear priorities, find root cause, select effective solutions, and manage the risks of implementation?

These questions are answered easily within a CAPA program that uses issue resolution processes that are linked to business processes and grounded in a human performance system that understands and supports compliance. FDA GMP and quality systems regulations and resource-efficient production are fundamentally compatible. Systematic corrective and preventive actions that optimize information technology systems with process thinking, can quickly build manufacturing efficiency that goes beyond compliance.