Overcome the five biggest barriers to group troubleshooting success

In today’s world of complex technology, dealing with multiple teams of hard-core specialists, it becomes more and more difficult to manage actions and stay in control. At Kepner-Tregoe (KT), our research and experience show that one specific role can provide a troubleshooting group with the clear focus and strong leadership that brings closure more quickly and initiates the actions to prevent a reoccurrence. That role is the facilitator.

In many organizations, the initial response to a major incident such as a service outage is to hold a meeting or set up a bridge call. The hope, obviously, is that the problem at hand can be solved by bringing together people with the right knowledge and experience. That these meetings often occur under high pressure – with services already down and stakeholders demanding resolution – makes achieving a positive outcome that much more difficult.

So, the way these meetings are run becomes extremely important. It not only determines whether they produce an effective solution, it also makes a difference in the emotional burden, financial cost and the reputation of the support organization.

Bridge calls and meetings benefit from strong leadership that keeps the group focused on the issues and avoids finger pointing or jumping to conclusions. Guidance and focus are just as important for meetings or calls which don’t take place under pressure but are convened to address ongoing problems. After all, it can be demotivating to the whole team to be working on an issue which has been open for many months only to discover that the wrong actions have been taken.

Answering questions such as the following, can help you determine the effectiveness of these meetings or their leadership:

- What progress was made during group troubleshooting sessions?

- How much clarity was gained from the meeting?

- To what extent were people involved?

- Were the right people present?

- Was there a free exchange of ideas or was the group forced to listen to the one who shouted the loudest?

Imagine yourself as the leader, or recall the last time you led a problem-solving group. How well do you think you were in control? What tips, tricks or magic did you use to assert your leadership and direct the group in the right direction? Do you know the most effective way to lead a group to a successful outcome?

This article will describe the role of a facilitator: the challenges organizations face which call for a facilitator’s help, the skills they need in order to stay in control and the benefits of having this role recognized within an organization.

What is a facilitator?

The dictionary defines a facilitator as someone who helps a group of people understand their common objectives and assists them in achieving them without taking a particular position in the discussion. In performing this function, a facilitator:

- Stays neutral, while guiding the group to consensus.

- Uses a structured process to gain an overview of the issue.

- Supports everyone to do their best thinking and work.

- Synergizes the group to work more effectively.

- Stimulates group creativity and encourages everyone to contribute.

A facilitator makes it easier for the group to work together as a team. In this sense, a facilitator acts like a catalyst. He or she does not wield a magic wand that will solve all the issues facing the group, but rather focuses the group on the process that leads towards a common resolution. The role of a facilitator is very much like a conductor in front of an orchestra.

Why is facilitation needed?

Now that we understand what a facilitator is, why is it valuable to distinguish this role and give people the skills to become a process facilitator?

Based on our research, the primary value of a skilled facilitator is the ability to lead groups to effective solutions by helping them to overcome the five biggest challenges in problem solving and decision making. In project meetings, shift-handovers, troubleshooting sessions, decision making bodies, operational meetings and crisis management situations, we have seen effective application of facilitator skills prove invaluable in overcoming these challenges.

Challenge 1: Thinking within the box

Groups assembled to solve an organizational problem typically consist of people who fill any one of four primary roles:

- Subject Matter Experts: those who have a deep, technical understanding of the issue at hand. They are needed for the correct and factual information they can provide for solving the problem. Subject matter experts may come from inside or from outside the company; for example, they could be partners, sub-contractors or suppliers.

- Problem Owner: the one person who has the authority and accountability to address a problem’s cause, and initiate the solution, thus resolving the problem and reversing its effects. This is the person who most feels the need to get the issue resolved, and who should be able to command the influence and budget to make that happen. The group could also include a person representing the end-customers who are affected by the problem, but do not have ownership of its cause or resolution.

- Third Parties: representatives from other teams – for example legal, insurance or marketing – who are interested in “who to blame”.

- Facilitator: the one who chairs the meeting and takes a leading role in managing the underlying structure of the problem resolution. The facilitator provides guidance for the group by keeping an oversight of the issue and managing the group’s troubleshooting process.

Because of the different viewpoints that people bring to these different roles, some of them may not be the best choice to serve as a facilitator.

Subject matter experts who attempt the facilitator role may have difficulty seeing beyond their particular areas of competency, knowledge and experience. Expertise in itself doesn’t make them the right facilitator. Often too focused on the content, experts may elaborate on the details of a specific operation and jump to incorrect conclusions.

Problem owners tend to manage the issue at hand from their own agenda: fix it quickly and push for the solution, with no interest in finding the root cause.

Third parties may not know much about the content, but are looking for someone to blame. As a result, they tend not to contribute to resolving the issue. Taking the lead as a facilitator, they would be interested only in finding a scapegoat.

Separating and clarifying these roles will minimize conflicts of interest within the group, help to avoid the development of biased solutions and ensure the following of a rational process that keeps all stakeholders involved. A facilitator may not need content knowledge, but he or she does need experience in the underlying processes and techniques to promote thinking outside the box and to help the group address the issue from different perspectives that its members bring to the discussion.

Challenge 2: Increasing technical complexity

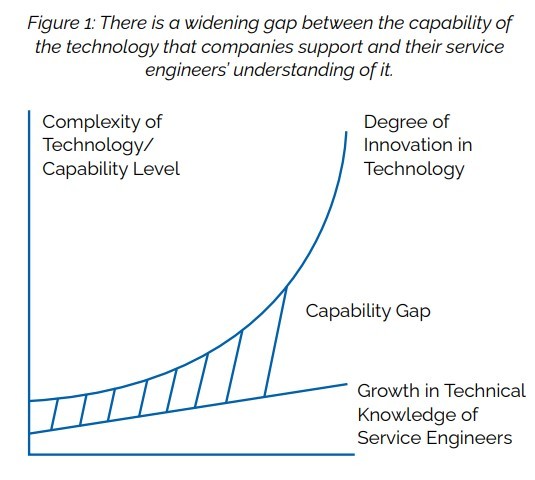

To manage their most complex or urgent issues, organizations most often appoint people with deep technical background and experience and long service in the company. It is a fact of life within IT service support organizations that (third-party) technologies, internal processes and new features and artifacts are constantly changing and growing increasingly complex.

“Everything is changing too rapidly, and no one can keep up with all the latest developments” is a common complaint heard from technicians and their management. Among some users, technological change and complexity can in fact, cause panic.

In a group troubleshooting situation, the problem of technical complexity and who actually understands it leads to an important question: is more technical knowledge directing you straight to the right solution or is it diverting you onto side tracks and away from your ultimate goal? [1, 2]

A facilitator guiding a highly technical discussion will use his or her skills to draw out the facts first, paving the path towards resolution, unravelling the complexity of the issue and directing the group where it needs to go. Perhaps more importantly, the facilitator will maintain the logic of where the discussion should not go.

Figure 1: There is a widening gap between the capability of the technology that companies support and their service engineers’ understanding of it.

Challenge 3: The solution that worked before

Subject matter experts naturally draw on their experience in solving problems. It’s understandable that their initial response to an apparently familiar problem would be along the lines of “I have seen this before … it must be this … ”

Is it possible, however, that instead of leading to a quick and accurate solution, the expert’s extensive knowledge and experience are in fact blocking their ability to solve the problem? Thinking they know the answer, they may jump to conclusions too quickly without proving their thinking. Circling around their own assumptions and conclusions, they dig the hole of a favorite possible cause deeper and deeper.

In neuroscience these tendencies are known as pattern recognition and emotional tagging [3]. Pattern recognition integrates as many as 30 different parts of the brain so that in a new situation we make assumptions based on prior experiences and judgment. In emotional tagging, emotional information becomes attached to the thoughts and experiences stored in our memories. This emotional information tells us whether to pay attention to something or not.

Pattern recognition and emotional tagging are at work when we assume that if a workaround was successful before, it should work again in what we see as a similar situation. The content of our heads prescribes our range of possible actions.

To use a computer analogy, we need to change the way we work with our available hardware (our brain) and the data stored in it (the existing, deeply learned patterns) by installing and using the correct operating software (or thinking approach). A facilitator who can do this will be able to avoid the pitfall of jumping to inappropriate conclusions.

Challenge 4: Poor quality of information

Most companies have in place incident response procedures for managing the escalation of incidents from initial report to eventual resolution. Typically, these procedures specify when during an incident to inform whom of an update to the “Incident Statement”.

In many organizations, these procedures often seem to have been created with the primary goal of updating management by specifying the impact of the problem, the expected time to restoration and so on, without specifying exactly what is going on. No clear context or reason is given for why certain actions are taken. Messages such as “I am busy working on it, called network specialist” or “all the branches in Scotland are down, hoping for service restoration at noon” give the receiver very little information or confidence, compared with a specific action report such as: “DB049 having time outs with ERRxyz, DB050/051 are OK. Working on further specifying the problem”.

In a group troubleshooting process, the management of stakeholders’ experience and expectations is critical. Stakeholders get upset when they perceive a lack of quality information and can pile even more pressure on the team that is trying to solve the problem. Chaos can ensue and overwhelm the incident management team should a key stakeholder take over due to a lack of confidence in how the incident is being managed. In many situations, this has led to huge numbers of people attending conference calls, in which only a very limited group of engineers are actually working on resolving the issue.

The facilitator using a predefined process will see that the group has the right information on which to make decisions, keep the group focused during such calls, control involvement of the right people and ensure that follow-up actions are defined and responsibilities taken.

Challenge 5: Lack of a common understanding of the issue

It is amazing to see how often people understand an issue far less than they think they do. This is easily discovered by reading what a worker wrote down on an incident ticket (or repeated in a bridge call) compared to what was really meant by the person communicating the original message.

Bogus conclusions are easily drawn on assumptions made by the reader of information who does not check the facts. Misunderstanding of the actual problem can guide the resolution team in the wrong direction. It is very hard for team members to get a real understanding of an issue when the people providing information assume cause-and-effect relationships which are not proven or speak in company jargon which is not fully understood.

Superior knowledge and understanding of customer issues and their resolution is possible only by using structured questioning techniques, checking facts versus assumptions and listening very carefully to what is being said and to what is not said. Before a problem can be solved, the facilitator’s first job is to lead a team of highly motivated, highly skilled and experienced individuals to reach a common understanding of the situation.

What are the right skills to help a facilitator stay in control?

It takes a specific set of skills to create oversight, avoid jumping to conclusions and manage a group.

Using a structured problem solving and decision making process

A facilitator will benefit from a rehearsed, reproducible process to manage and stay in control of the group’s analysis of a problem. A standard way of working will:

- Help to get all people on board and working together (instead of looking for blame or losing oneself in technical expertise).

- Provide clear guidance to the group.

- Provide something recognizably “independent” that will help the facilitator focus the group on what is needed at that moment and stay out of content.

According to our research, the lack of a structured troubleshooting process is often one of the reasons that certain problems stay open for a long time. Workers may be misusing problem tickets to share statements about organizational issues that are vague, based upon assumptions or possibly not even related to the problem. Invalid conclusions may then be drawn based on this misinformation.

The task for a facilitator is to bring structure to situations such as this. An effective facilitator will use an analytical process to define the facts, filter out and appropriately handle opinions, challenge assumptions, provide summaries and ensure that everybody is appropriately involved.

Returning to our computer-and-brain analogy, for over 60 years, Kepner-Tregoe’s expertise in Rational Thinking has proven to be the right “software” for our brains to operate correctly and follow a structured process, even when under pressure [4]. The fundamental idea is that effective trouble-shooters and decision-makers reach conclusions by following a series of clearly defined steps and principles. They also know what to do when actions do not have the desired outcome: they look ahead and prepare next steps to keep working towards a resolution. The KT processes provide the how for the company’s procedures for handling problems and incidents.

Of course, the more people who are familiar with the same operating software, the more effective a team’s collaboration will be and the easier it will be for a facilitator and the team to make progress towards a resolution.

Using a Facilitation Process

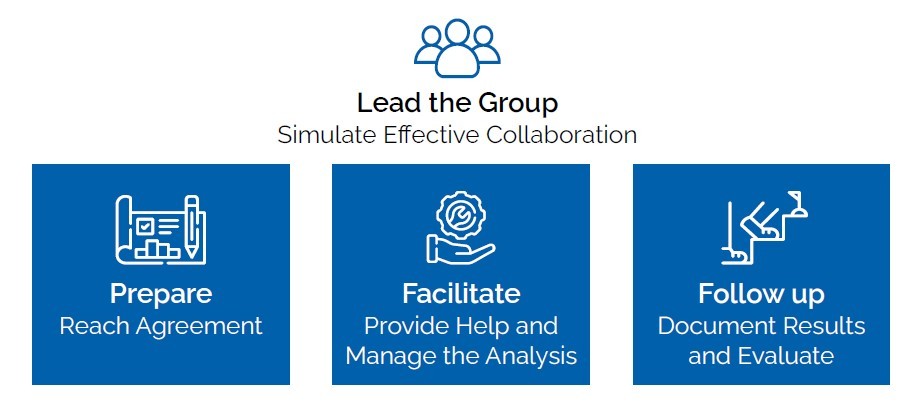

A facilitator must be able to prepare, lead and follow up on the process facilitation sessions. The tasks required to complete each stage are easily defined:

- Prepare the session: Set the scope and get clarification on the issue to be resolved, define objectives and constraints, ensure the right people will be involved and plan the session logistically.

- Facilitate the session: Start, and lead the meeting by using a structured process. Making sure that everyone’s thinking is kept visible and focus on the analysis is kept.

- Follow up the session: Document progress and define follow-up actions.

- Lead the group: Stimulating effective collaboration by involving everybody in order to get balanced participation, regularly summarizing to keep oversight, managing conflict and seeking consensus.

Figure 2: KT’s Facilitation Process

Having the right hardware: minimum specifications for a facilitator

Among the most fundamental required skills, a facilitator must be able to:

- Ask open ended questions designed to elicit more meaningful responses.

- Listen actively to what is being said (and not said).

- Work with a range of styles and personalities.

- Develop relations quickly.

- Take the lead in a group of enthusiastic experts.

Furthermore, a basic understanding of the business and how organizations work will help build the facilitator’s credibility. The person should be open to self reflection and analysis in order to improve themselves and continuously increase their skills.

What’s Next?

By recognizing the role of a facilitator, organizations will make more effective use of the existing knowledge and experience available in their organization. Problems which have been persistently stuck can get the push that will move them toward resolution. Major incident calls can gain the oversight and structure of the facilitator’s strong leadership.

Having the fundamental requirements in place can help assure the success of the facilitator role in your organization:

- Equip the facilitator with the right facilitation processes and skills.

- Set up the right infrastructure and physical environment.

- Ensure management commitment.

- Provide the facilitator with continuous feedback.

What can you accomplish with these elements in place? Well, these are the very same processes followed by the engineers at NASA, who – under the most extreme pressure imaginable – solved what went wrong aboard Apollo XIII, developed a solution and brought the astronauts safely home [5]. So whatever problems are standing in the way of your organization’s success, with an effective facilitator helping you achieve a solution, the sky is quite literally the limit.

References

[1] Joosten, M.H.M. 2010. It’s all becoming too complex!

[2] Goldenstern, C. 2009. Closing the 21st Century Service Capability Gap, Kepner-Tregoe.

[3] Campbell, A., Whitehead, J., Finkelstein, S. February 2009. Why good leaders make bad decisions, Harvard Business Review.

[4] Kepner, C. and Tregoe, B. 1997. The New Rational Manager, Princeton Research Press.

[5] Ibid. p.57. Trouble Aboard Apollo XIII.